21/12/2016

When Indian contemporary art was going big and the spaces in and around Kochi were being acquired by land as well as art ‘developers’ during the first decade of the new millennium, a few artists in the city were turning their attention to the silent cries of the nature.

They had only colors and brushes. So they captured the throes of nature on their canvases, not only as a deep prayer for the wounded land, but as a heartfelt confession on behalf of the mankind.

Mathai K.T. is one of those artists who turned himself as a human receiver to relay the messages of nature -- in lines, forms and colors, from his humble hamlet called Karakunnu in Mulanthuruthy, Ernakulum.

Mathai is inconspicuous even within the artist crowd. His demeanour is less asserting as he exudes the feel of a ‘literature kind.’ He stands silent before the spectacles that the movers and shakers of contemporary art create within the city. He equally maintains a detachment from the sloganeering types who demand conservation of environment and preservation of natural order. Educated from the famous RLV College of Fine Arts, Thrippunithura, Mathai, true to his nature, also held himself back from all the cut-throat competitions in the art market that started in the 1990s.

There were the Van Gogh types and Andy Warhol types of artists in Kerala those days. The former suffered silently and used their suffering as a tool to live through the hard times, and the latter wanted a flamboyant life style and went looking for jobs that provided them with creature comforts and luxury. A third category, the Cezanne Types, I would say, either migrated to other art centres or remained in their home towns doing art and supporting themselves by engaging in odd jobs. Their life was precarious, for one could fall to either side where Van Goghs and Warhols lived. By the time the Indian art market boomed, it took no time for the Van Goghs to turn Warhols, and interestingly, many Warhols of earlier times were reduced to Van Goghs. Mathai remained in the Cezanne mode, looking at nature and painting it to his heart’s fill while the land mafia was gnawing away the beautiful earth around his village.

The view from his veranda was something that had shaped Mathai’s aesthetical temperament. Like the opening lines of Changampuzha’s ‘Ramanan,’ the elegiac poem, the mornings were fabulous and evenings quite wistful. From this ethos, Mathai knew what his art should be like. After his education, Mathai went on to set up a graphic design studio to eke out a living, and also to keep himself away from the competition.

Mathai made his first impression in the art scene with his attractive landscapes in deep greens, blues, browns and reds. But the artist, who is deeply spiritual and fairly critical of religion, knew the wailing symphony that he had been creating. The more one looked at Mathai’s works, the more one came to know that the reds were blood, or earth’s wounds caused by monstrous machines. More than any photographic documentation, a study of Mathai’s paintings over the last two decades would reveal how a sylvan landscape has been changed into a graveyard of gaping holes. But Mathai doesn’t want his works to protest nor does he want to be a protesting artist. He just wants to flag out the things that we have lost.

Still, Mathai did protest once. The gesture was so subtle that the whole village of Karakunnu joined him. The artist started a procession from the courtyard of the village church, which often comes to play a pivotal imagery in his paintings, with a mango sapling in his cupped palms. The village joined him with drums and flags. The procession held in 2011 was spontaneous, and the ‘thorthu’ that Mathai tied around his head gave him an indelible identity of a farmer. He walked along streets as the villagers kept joining him. They reached a place where once a mangrove stood. He planted the sapling there and that was it. Mathai never did performance art again. If we press him, he would say he never intended to do one and what he did in 2011 was a heartfelt act which wouldn’t have found an expression in any other medium.

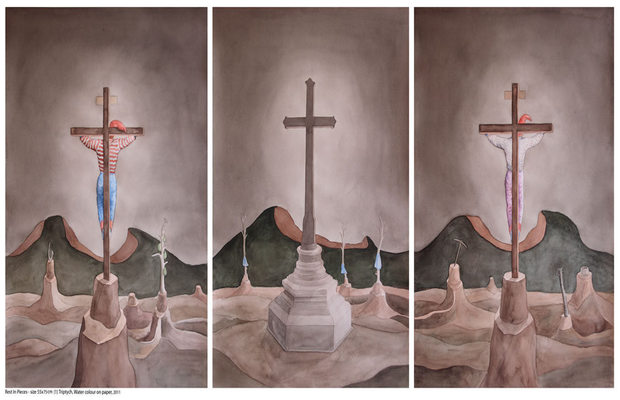

Has Mathai grown sad? He doesn’t look so: he remains calm, composed, almost ego-less and most of the time silent. Has he become cynical? A closer look reveals that some kind of a foreboding sense of gloom has come upon the works of Mathai. From greens, blues, reds and browns, Mathai’s palette has drastically taken a turn to black and greys. And his sense of irony has introduced a set of clowns hovering around the village landscape which by now has been pushed to the background toward the horizon of his paintings. A bier standing alone, as luminous as a ghostly gloss, right in the middle of a dark path with contours of the surrounding areas melting into the pervading darkness has become a favourite topic of Mathai. An artist with an inclination to the Christian way of spiritualism, Mathai has employed several telling symbols of church and Christianity in his works.

But slowly his works are changing. From a definitive religion with its organizational structure intact, Mathai moves to a more liberal Sufi space where a Godly figure cradles a mother pig, a lowly symbol raised to the level of divinity. The protagonist is a philosopher king who could lead by example and not by force. The philosophical maturity of Mathai is palpable in his works while his style and technique have gone into the layers of subtleties.

And the landscapes have started coming back once again to his works, now not as the landscape of Karakunnu, but as the landscape that one carries within oneself.