24/11/2016

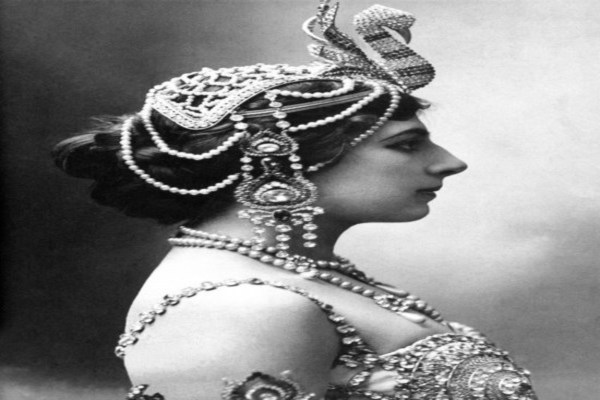

It took me three hours to finish reading ‘The Spy,’ Paulo Coelho’s latest novel. Not really a page turner, but the 180 pages of fiction based on the true story of Mata Hari, the spy who was executed on 14th October 1916, is a sympathetic retake on the woman’s life. Marguerite Gertrude Zelle aka Mata Hari was a Dutch woman who became a double agent for the warring Germany and France. Mata Hari became famous as a dancer and seductress in the high circles of Paris, which gave her passport to state secrets, as alleged by her inquisitors.

The novel is short and crisp. While reading it, one feels Mata Hari is a wronged woman by a society governed and led by the patriarchal values. Margaretha (the spelling used in the novel) was a woman ahead of her times; perhaps that quality came from the fact that unlike many other women of her time, she didn’t want to live an oppressed life, initially by the parents, then by the school and eventually by the husband and family. However, young Margaretha was confused about her own self, like many other female protagonists in Coelho’s novels. Like others, she too aspired for a good life. Her body was violated by the principal of her school, when she was just sixteen years old. Since then, for Margaretha sex had become a painful and abominable thing, but she realized later that she could return it in favour of the luxuries she received from the rich and powerful.

Margaretha marries an army man and goes to Java where her husband is deputed. There the philandering army men make their wives mere witnesses to their womanizing, almost crushing their subjectivities as individuals. The wife of one Major Andreas, having been insulted by her husband as he flirts openly with a Javanese dancer, takes out her pistol and shoots herself. She dies in the hands of Margaretha. The look in the eyes of the dying lady, suddenly ‘enlightens’ her and she decides to leave Java and head back to Holland. Margaretha now knows she wants her freedom. She also knows she could use her body to gain access to anywhere; she migrates to Paris by flirting with a French officer. She chooses the life of a dancer by pretending to be an exotic dancer from the east and adopts the name, Mata Hari.

Mata Hari is now a much written about personality of Paris and everyone wants to be with her. In one of the episodes, we see how a young artist named Pablo Picasso trying to flirt with her, and as she understands, to ‘bed’ her. But she likes an Italian artist, Modigliani, who treats her with due dignity. She goes through a series of bedrooms of the rich and powerful and suddenly is ceased by the fear of getting old. She gets an invitation to perform in Berlin and by the time she is on her first platform there, the war between Germany and France starts. Now Margaretha has to leave the country. In Hague, she decides to become a German spy and once back in Paris, she agrees to be a French Spy, thus becoming a double agent. The intrigues finally lead her to the prison, and all those high ranking men who have slept with her, disown her. Finally, she is executed by the firing squad. Not because there were evidences against her, but her acquittal would’ve left many men with grease on their faces.

Technically speaking, the Spy is an epistolary novel; it is comprised of two long letters written by Mata Hari from the Saint-Lazare prison, addressing her advocate Maitre Cluent, and the letter written by Cluent explaining his angst in not being able to save her from the firing squad. The narrative is familiar as in other novels of Coelho. A sinning or sinned woman as the central character and the author pitches in to say (through his narrative) that she isn’t a sinner but our perspective is what making her a sinner. Mata Hari stands closer to Maria of his early novel ‘Eleven Minutes.’ Maria too is a woman who pawns her body to earn a good life and goes through tremendous physical and mental tortures to realize her own self/worth.

While reading `The Spy,' somehow I was constantly reminded of Kuriedathu Tathri, a Malayalee Brahmin woman, almost a contemporary to Mata Hari. Kuriedathu Tathri was violated by a middle aged Brahmin, when she was hardly ten years old. Then she was forced to marry the rapist’s younger brother. Then the brothers together ‘presented’ her to many men. In the meanwhile, Tathri too used her body to assert her rights. She then became a problem for the Brahmin community and was made to go through a trial which was called ‘Smartha Vicharam.’ In the trial conducted in 1905, Tathri revealed all the 66 men who had sex with her for almost fourteen years. Instead of punishing those men, the society was successful in excommunicating her.

Paulo Coelho has been a delightful read till he wrote his novel, ‘Adultery.’ It was a disaster. His early novels, Alchemist, The Zahir, Manual of the Warrior of Light and so on stand apart because of their pure spiritual quest. The sex and sexuality that Coelho uses in his later novels have become very predictable. Though full of quotable quotes on life, freedom and love, and above all, on domestic and platonic relationships, `The Spy’ seems to be a rushed one. The subdued, calm and whispering tone of Coelho could be heard throughout the novel, which is detrimental to a literary narrative. For an Indian reader with some spiritual introduction to the Hindu/Indian philosophical diversities, Coelho’s takes on humanity, love and freedom look very text-bookish, even though it would be quite exciting for the Euro-American readers who may need additional environments to feel spirituality. I think the popularity of Coelho in India shows nothing but our growing interest in materialism and the growing gap from the spiritual foundations of (Indian) life.