06/10/2016

I was amidst a slide presentation by an artist when somebody’s status feed in Facebook informed that Yusuf Arakkal is no more. Suddenly I remembered a verandah of some building, way back in 1995. It was a national artist camp initiated by the Kerala Chitrakala Parishath commemorating T. V. Balakrishnan Nair. Arakkal was playing his magic on a canvas. I, then a 19-year-old girl and member of that camp, was closely observing him. It was an interesting technique of creating texture on the canvas: not pasting thick blobs of color, but smearing plenty of linseed oil and less of the clay called paint. Those days, I was an admirer of thick application of colors. But then I realized that lavishness can also be obtained using oil. It was a new knowledge. Then I remembered somebody else too doing so. It was S.G. Vasudev. When two years back I visited a show at gallery Sumukha in Bangalore, Vasudev was following the same technique.

Yes, modern artists struggle to arrive at a formal language for themselves. Once they find a style, then that style defines them. They experiment within the confinements of that technical signature. Arakkal, in his 50s then, had already arrived at his ‘signature style.’ Finding me so curious, he told me with lots of affection: ‘Don’t confine to Kerala. You will find art far away’!

He was right. Kerala had a time when its fresh and ambitious young minds, in search of a life as artists, were all migrating to other Indian cities such as Chennai, Bangalore, Mumbai and New Delhi. All of them were carrying the fire of individualism. Arakkal belongs to that time. Each of these cities has created their own texture to the idea of modern art in India. Perhaps one could say, he belonged to a generation of artists who localized and diversified the idea of Indian modern art for various reasons. Arakkal and Balan Nambiar are the two influential artists who engaged themselves with Bangalore, its emerging industries and buzzing economy amidst a middle-class pleasantry and pristine landscape in 1960s and 70s. M.F. Hussain was one such person who was engaging with Mumbai, with more potential national narratives of India, its mythologies and politics of a Congress ideology. Down south, K.C.S Panikker was proposing some practical means to engage with the traditions and mysteries of India in a modern language.

Today, the conviction of modern is supposed to be a ‘given’ idea, and the challenge is to find a new restructured reason for anything, anywhere. So the new generation has plenty of opportunities and a wide variety of options to work as an artist. Anybody with unflinching conviction of modernism in art in the latter half of the 20th century had quite a tough time because their language was not a continuity of any tradition, but a break. Surviving as a common man was one thing and emerging as an artist was another.

With not so conducive conditions at home after an untimely death of his parents, Arakkal first landed in Bangalore as a jobseeker. He emerged as an aerospace designer. But a full time career as an artist was a result of a few confident choices he made out of his solitary rowing of his life. It’s visible more in the very introspective language of his art works. Compared with Mumbai and Delhi, the south Indian scenario of art galleries and enterprising art buyers was still bleak. Sara Abraham who initiated Kalayatra, India’s first roving art gallery, was his elder contemporary, who collected many of his early works.

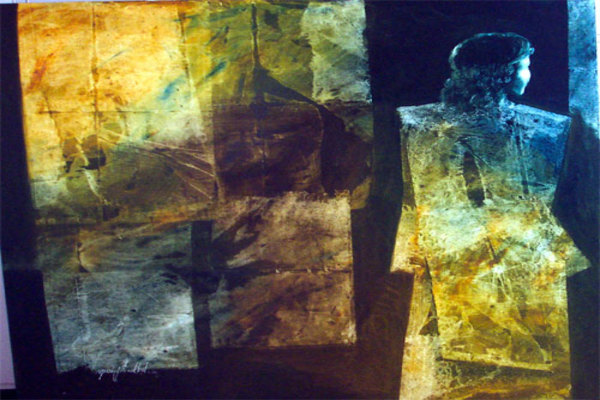

Arakkal’s sculptural medium of work often represented a modern industrial world. His artistic contribution seems to instill the narratives that celebrated the scientific discoveries on which industrial developments depended for their existence. The formal aesthetic connect he created with scientific world and the industrial economy of an emerging city like Bangalore, could interact in a way with the larger modern scenario across places. The private entrepreneurs, possible promoters of art, noticed him for his narratives that had a peculiar connect with him.

Modern artists by all means interacted not with the common man and his kitsch taste. Arakkal initiated certain intellectual negotiation. How far things were uncompromising was up to the artist’s choices. Nambiar connected the geometric quality of abstraction with the ever-present geometric attitude in Indian folk and performance practices. But Arakkal didn’t embrace much of mysterious connects specific to the traditions. He developed a decorative narrative, be it out-door public sculpture format or an interior wall fixture or installation. An educated person, though uninitiated to art history, would connect with this because it had fewer burden of mystery and tradition. This could’ve made Arakkal less pretentious and relatively popular among art-lovers.

This dis-interest in artificial mysteries of a typical modern artist also helped him communicate with more people in the contemporary parallel scenario of Kerala. It was highly dominated by literary people where artists generally could only illustrate characters of famous literary lives in the writer’s fiction. Arakkal adapted the characters of Vaikom Muhammad Basheer, but in his own way. His Basheer series had a sundry attitude of shadows and sunshine. Those works removed the clarity of the literary contexts in Basheer and pushed them as human bodies caught in the luminosity of life and its events, much the same way as any man in the modern era could’ve existed. All so context-less and improvising.

Art lovers will miss Arakkal. There are still many stories untold, of the survival of the modern Indian artist.