03/10/2016

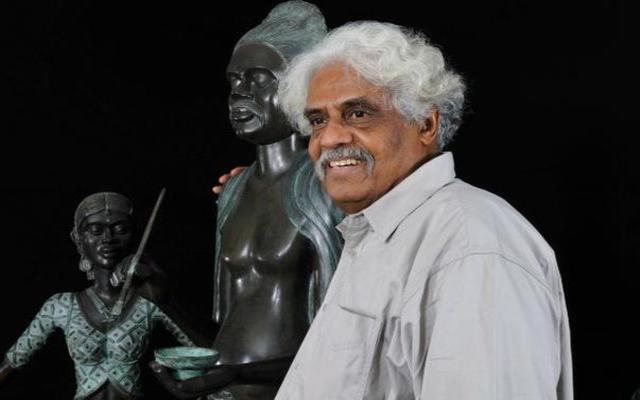

“This is a girl on a swing,” says artist A. Ramachandran with a mischievous smile. The 81-year-old tall and charismatic artist stands before his latest work that is in its initial stages. The image is decipherable in his favourite ochre color.

In corduroy trousers and a yellow apron, there is nothing that makes Ramachandran a typical Malayalee artist. However, there is a lot of `Malayaleeness’ in Ramachandran: his extensive research on Kerala’s mural traditions; his post-graduation in Malayalam literature; his training in Carnatic music; and his detached interest in all that define `Malayaleeness,’ including his assertion that he would explain things in Malayalam and his realization that he has been talking in English for almost three hours.

Ramachandran lives in a three-storied building, custom designed by the artist himself in early 1980s, in the Bharti Artists’ Colony in East Delhi. He is all set to go to Bengaluru where his first ever retrospective exhibition in South India is slated to take place on Oct. 5. Presented by Delhi’s Vadehra Art Gallery and curated by the noted art historian R. Sivakumar, this retrospective is mounted at the National Gallery of Modern Art at the historical Manikyavelu Mansions.

For the last couple of decades, Ramachandran’s works have become metaphorical and allegorical, stressing on the two dimensional nature of paintings with colours carefully applied on the canvas with a skilled traditional craftsman’s patience and precision. They look like scenes culled from sylvan rural landscapes where careless men and women rejoice. In the process, Ramachandran lifts himself up to oversee the world of his own making, of metaphors, like a Gandharva, becoming a part of the paintings.

This inclusion of the self in the works of Ramachandran is a radical departure from modern practices where the self of the artist is often represented in definitive self-portraits or by the rendering of the signature. Ramachandran takes the modern practice of painting to its traditional roots where the painter includes himself in the divine as well as regal narratives as an inconspicuous presence discernable to trained eyes -- as a devotee or a minor deity, perhaps drawing inspiration from his studies of Indian murals, particularly those of Kerala. Of late, the self-inclusion within the pictorial narratives has taken a different turn; instead of a hovering Gandharva, Ramachandran has transformed himself into an unborn child safely sleeping inside the womb (which is represented by an earthen pot), quite oblivious of the turmoil of the material world. Seen from a mythological ken, it could be interpreted as the sleep of the God who dreams about a world of beauty. And seen from a materialistic point of view, one could also read these images as the artistic reluctance to indulge and involve in the chaos in the world, ridden and riddled by too many complex relationships between people and states.

Those who know the early works of Ramachandran who had just come to Delhi from his studies and researches in Santiniketan, may be surprised to see the departures that the artist has taken in his recent works. An acerbic critique could position him as an escapist who lives and creates apolitical rural fantasies. “Yes, I stopped being political long back,” says Ramachandran. “I had been painting tortured human beings, faceless people and desecrated bodies. I had been sarcastically portraying the political tormentors of the world from 1960s to early 1980s. I used to read Dostoyevsky to keep myself in the dark mood. Slowly I realized that I need not create a dark mood, because in my personal life I was comfortable, and the political climate was already dark enough. I was caught between this comfort and confusion only to realize much earlier that artistic pursuit is not sloganeering but expressing one’s life through a medium. I wanted to be sincere to my works. So I stopped deliberately being a proponent of dark realities.”

He looks deeply at the painting on the wall: “Of course, my works are not the representations of political realities. In 1984, I saw Sikh brothers being butchered right in front of my eyes. I was standing at my terrace. I was helpless. My art changed that day. I ceased to be political in art because I realized that art cannot stop political violence though violence can result into a few works of art.”

The government of India awarded Ramachandran with Padma Bhushan in 2005. “One needs huge awards like that to be recognized in Kerala,” he says. Ramachandran once lived with his artist wife Chameli Ramachandran in Thiruvananthapuram. Every day in the elevator of the apartment, they used to meet other elderly couples who showed no signs of familiarity. The day they saw Ramachandran’s face pasted all over newspapers and television channels, people in the apartment realized this man was living in their midst for almost three months. “I had to attend two receptions in the same compound in the same evening. Everyone knew me as a friend all of a sudden,” laughs Ramachandran heartily. He sold his Thiruvananthapuram flat a few years back after accepting the fact that he wouldn’t be able to live as a ‘naturalized’ Malayalee there. A man who loves the writings of Vaikom Muhammad Basheer, N. Mohanan, V.K.N. and O.V. Vijayan, Ramachandran says that he loves prose than poetry. “I write my own poetry in my paintings.”

The stairway that leads to the first floor studio in his Delhi house gives one an ample vision of the displays on the walls: miniatures and oleographs. Ramachandran is an avid collector of miniature paintings from all over India. “I use Whatsapp for receiving gossips and miniature images,” Ramachandran says. On the floor, one could see some ancient wooden sculptures that curiously depict Christian themes; Ramachandran has one of the best collections of wooden Christian sculptures, mostly sourced from Kerala.

Let’s go back to his initial statement, “This is a girl on a swing.” Even if a painting is as straight as this, people ask the artist, “What’s the meaning of it?” “This is a girl on a swing,” asserts Ramachandran and points at a pivotal issue that has been haunting our art scene for long. Even the simplest and straightest of the images are not seen simple and straight. “That’s a big problem and a hurdle to be removed in the appreciation of art. A work of art has intrinsic meanings and the viewer need not necessarily be going by the artistic meanings. For an artistic like me, a painting is just a thing of visual pleasure.” I look at the painting. Yes, it is a girl on a swing.