19/09/2016

One of the most brilliant minds of 20th century America also bore the indelible stigma of the country’s biggest act of blunder caused by its imperialist foreign policy. Robert McNamara (1916 – 2009) went to Harvard armed with a perfect GMAT score. President of Ford Motor at 44, he was the U.S. Secretary of Defense through seven crucial years of the Vietnam War. The blood of millions was on his hands, something he couldn’t wash away through rehabilitation later as the World Bank President. His 1995 autobiography ‘In Retrospect’ is subtitled ‘The Tragedy and Lessons of the Vietnam War,’ a sad but telling indictment of the fall from grace of a certain genius.

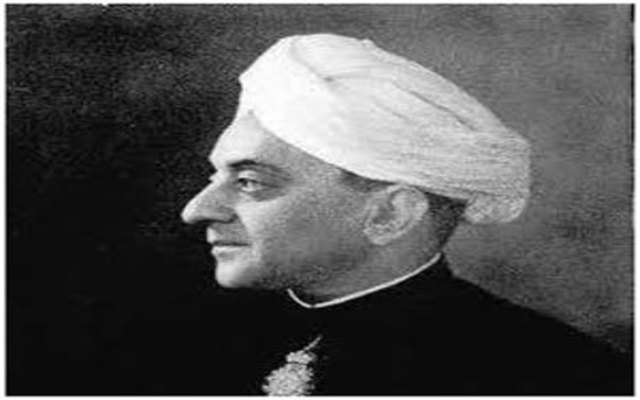

Before the world heard of McNamara, there reigned in the South Indian kingdom of Travancore a Dewan whose dazzling brilliance and foresight are yet to be fully fathomed by a people who benefitted from it, shrouded as he is in a McNamaran cloud of military action taken during his term. Half a century has elapsed since the passing away of Sir Chetpat Pattabhi Ramaswamy Iyer (1879 – 1966), but the legacy he bequeathed us is too formidable to be wished away. In October 1946 when a revolting mob of communists in Punnapra - Vayalar defied curfew, turned uncontrollably violent, attacked police stations and murdered policemen, the Dewan, in his capacity as Commander of the Travancore Army, issued firing orders resulting in 100s of deaths.

CP ruled with an iron hand. When K.C. Mamman Mappilai, the powerful baron of Manorama newspaper evaded income tax due by his Travancore National Quilon Bank, he was thrown in jail and his paper banned. Around this time legendary writer Vaikom Muhammed Basheer wrote a series of articles against CP’s rule and published them in book form as ‘Dharmarajyam.’ It was banned and saw the light of the day only 60 years later. The incidents gave CP a bad press thanks to the popularity of those at the receiving end.

CP had three distinct and distinguished phases of his career, as a lawyer, Dewan or Prime Minister of a kingdom, and an academician. Born in North Arcot in Tamil Nadu, CP excelled in his studies and shone in his legal career. By 40, he was appointed Advocate General of Madras. He left his lucrative practice to become Travancore Dewan. He was paid 6000 rupees a month and put up at the Bhakti Vilas palace. Earlier as Political Advisor to Travancore, CP had successfully fought a case for them against Madras in the Periyar water dispute. CP’s was the lone voice that opposed the granting of permission to Tamil Nadu to generate electricity from the Mullaperiyar Dam. This is corroborated by the Travancore Manual of those days. The Achutha Menon Ministry later disregarded his advice and the state is paying the price for it.

CP’s granddaughter Shakunathala Jagannathan who was Deputy Director General of Tourism is the author of ‘Sir CP Remembered,’ a wonderful compendium on her thaatha. But for a more juicer account one has to turn to A. Raghu’s delightful biography, ‘Duty, Destiny and Glory.’

Several women came to play a part in the charismatic CP’s life. His wife Seetha Ammal who died aged 44 was a resourceful woman who designed a four-colored silk sari that gained popularity as CP Check Sari. While serving in the Viceroy Lord Willingdon’s Executive council for five years from 1931 CP became great friends with his wife Lady Marie Willingdon who was to play a key role in his career. As Dewan, he struck a strong bond with the Queen Mother Sethu Parvathi Bai which left tongues wagging. The young Maharajah being a bit effete it was effectively the mother and the minister who took vital decisions as Manu S. Pillai underscores in his chronicle of the lives of the Travancore Queens, The Ivory Throne. Raghu mentions CP’s close friendship with Philippa Burrell, an English lady several years his junior who was by his side when he breathed his last at Oxford during a trip to research for his proposed book ‘A History of My Times.’ I reserve the most important woman for the last, Annie Besant. Curiously their encounter started as rivals when CP fought and won a case for the father of future seer J. Krishnamurti who sought custody of his son from Besant and the Theosophists. Despite losing her case, the Irishwoman was so impressed by CP that she asked him to join her in the Home Rule League, triggering a long association. As Secretary of the League, CP took exception to Gandhi’s non-cooperation and khadi movement. For one thing it would deprive the Kanchipuram silk weavers of their livelihood, he argued. CP awed the visiting British writer Somerset Maugham with his erudition such that he contributed an eulogy on him in ‘CP by His Contemporaries’ and named a character in his novel ‘A Narrow Corner’ after him. The Maharajah bestowed the title of Sachivottama on CP, a precedent for which can be found not in history but in mythology when Rama termed Hanuman thus. The life of CP in a nutshell is about steadfast loyalty to one’s duty. Commitment was sacrosanct. Dharma reigned above everything else.

Did CP have a disdain for communism? CP was skeptical about joining the Indian Union due to Jawaharlal Nehru’s sway toward the Soviets. Plus Travancore was strategic given the rich mineral deposits along its long coastline and could stake a valid claim for separate nation. Jawaharlal whose father Motilal once took the legal services of a young CP, saw red at the pugnacity of the latter. CP retracted on the American model separate nation stance after meeting the Viceroy Mountbatten in July 1947. He handed over the file with the green signal for accession to India to the Maharaja on 21st of that month. The king procrastinated.

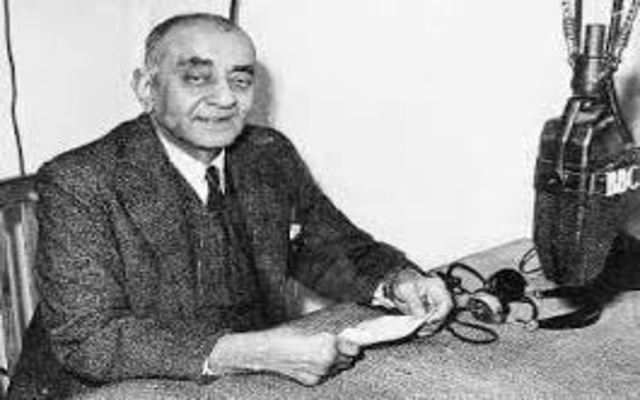

Meantime, K.C.S. Mani of the Travancore Socialist Party, an early version of the RSP, attempted to assassinate CP on the night of 25th at Swathi Thirunal Sangeetha College. His breath control coming from years of yoga practice saved CP his life and he went on to last another 19 years. It is a myth that CP fled and the king was forced to accede. On 19th August CP left Travancore for his retreat in Ooty. From there he set out on a lecture tour of South American countries. He proceeded to the U.S. and met President Harry Truman. In 1955, CP embarked on another glorious chapter in his life, that of a full-fledged academician. Nobody before him had donned two Vice-Chancellorships simultaneously as CP did of Annamalai University and Banaras Hindu University. He had been the founding VC of Travancore University, present day Kerala University, the Senate Hall of which adorns his stately portrait. At least one person alive will vouch for his patronage. At Annamalai CP paved the way for Padma Subhramaniam to become the first PhD holder in dance anywhere. Earlier he had made a quaintly surprised Shemmangudi in his thirties the Principal of Swathi Thirunal Music College. Before you read caste undertones, CP appointed Mrs. Anna Chandy as the first woman District Judge in the land and Mary Poonen Lukose as the first woman Surgeon-General. He inaugurated a mosque in Kollam. As Saroja Sundararajan’s biography of CP informs us, he had invited Albert Einstein to be the VC of Travancore University but the great scientist chose Princeton instead.

The Himalayan intellect of CP is reminiscent of a contemporary Tamil Brahmin scholar who strode like a colossus in Malayalam literature. Not only was Ulloor S. Parameswara Iyer (1877 – 1949) an epic poet, but he also compiled a five volume History of Malayalam Literature, in which he magnanimously gave even budding writers younger than him pride of place. If Ulloor worshipped at the sanctum sanctorum of Goddess Saraswati he was no minnow in his official career, rising to become Dewan-Peshkar or today’s Chief Secretary. CP, a deep scholar of Vedanta and classics of the East and West and a connoisseur of arts and culture in general, was a perfect complement to the writer of Premasangeetham. CP should’ve been Indian President, like his friend the philosopher-statesman Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan. The man who British Prime Minister Clement Atlee remarked would easily have walked in to the PM’s seat in 10 Downing Street had he been born in England, detached himself from seats of power. It was left to his son C.R. Pattabhi Raman to become a Union Minister, when he handled Law in Nehru’s Cabinet. Pattabhi snapped the dashing profile picture of his father that adorns the cover of two of the books on him I have mentioned here.

Among the many costly mistakes made by free India’s governments, the first was in not sending CP to advocate India’s cause in the UN vis-à-vis Kashmir. After visiting China in 1955 as a delegate of the UGC, CP sent warning signals to Nehru which was unfortunately not heeded, and the nation paid a heavy price for it through the Sino-Indian War of 1962. When Article 356 was misused in 1959 to dismiss the E.M.S. government in Kerala, the legal eagle in him was the first to oppose the action, never mind the fact that it was a Communist government that got axed. CP was spiritually grounded and detached to material wealth accumulation. He contributed heavily to charity throughout his life. He started the Vanchi Poor Fund after witnessing a boy sleeping on the pavement near the Secretariat. It’s unfair to credit the legion achievements of the Chithira Thirunal era to the ruler and treat the Dewan as a whipping boy to attribute all its ills to. The distinguished historian A. Sreedhara Menon is clear on that count in his work ‘Triumph and Tragedy in Travancore: Annals of Sir CP's Sixteen Years.’ Every achievement of the period starting from the epoch making Temple Entry Proclamation has the stamp of CP on it. Projects like Pallivasal Hydroelectric, Titanium and Rayon wouldn’t have materialized without CP at the helm. The grand reception the masses accorded to CP when he returned to Travancore in 1960 was as much a display of longing for a great administrator as revulsion of the communism experiment they had to undergo. He was taken all the way to Kanyakumari along the 88 kilometer cement highway built by him, to a rousing welcome.

Unlike Robert McNamara, CP never had any reason to regret his military action against the Communists. Leafing through his Biographical Vistas, an account of great men that he brought out in the final year of his life, I read his take on communists, ‘…….Effective planning is possible only when subversive and disruptive forces are under strict control and the danger of the Communist movement lies, not so much in what may be theoretically understandable ideology but in its intrinsic doctrine of strife as an essential element of political and social existence…….’ His conviction that the communist propensity to shatter everything is hardly backed by any remolding, rings ominously true even fifty years later.

It’s high time we recognized the visionaries who shaped our destinies and give them their rightful due. Today, the dearth of icons in public life is such that we turn heroes of civil servants who merely carry out their mundane tasks without fear or favor! It may not be preposterous to suggest that we return to Sir CP, Machiavellian shadows be damned.